The Voyage of the Restauration – Crossings 200

Welcome to our Virtual Voyage as we journey along with the replica of the Restauration that sets sail from Stavanger to New York.

Each week we will add a stop on our way. Be sure to check back weekly to learn more.

Click on the ship and red markers to learn about the 200th anniversary voyage!

Week 1: The Launch

Overview of Migration to America

Few events in Norwegian history have met with greater fascination from Norwegians and Norwegian emigrants than the story of the Restauration and the crossing to America. The course of the departure, the arduous journey across the Atlantic and the drama the emigrants experienced upon arrival in New York have been described in countless novels and non-fiction books. The Restauration is considered to be the “Norwegian Mayflower.”

The voyage in 1825 marked the beginning of organized Norwegian emigration to America, with more than 850,000 Norwegians following in the wake of the Restauration over the next hundred years.

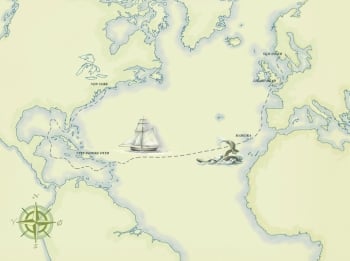

The Restauration crossed the North Sea on a southwesterly course, passing through the English Channel, and continuing south to Madeira. On this Portuguese archipelago west of Morocco, they stopped over and took on provisions before the captain set off west to cross the Atlantic. This southern route was carefully planned and was a common route for merchant ships sailing between Europe and America. It had its clear advantages in that it could take advantage of the trade winds and sail into a warmer climate.

On July 4, 2025, a replica of the Restauration sets sail from Stavanger, seen off by HM King Harald and HM Queen Sonja, other members of the royal family, dignitaries, citizens of Stavanger, members of Sons of Norway and a large contingent of well-wishers.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Sources:

https://www.restauration.no/

https://ryfylketrebaat.no/

Week 2: The Name

Cleng Peerson and the First Wave of Emigration to North America

In 1821, Klein Pedersen Hesthammer made a research trip to the United States to prepare everything for Norwegian emigrants in collaboration with American Quakers. He traveled with a man from Finnøy, Knut Olson Eide.

Klein Pedersen – or Cleng Peerson, as he came to call himself in America, used the time to familiarize himself with the country and the conditions there. Among other things, he found an area around Kendall in Orleans County on Lake Ontario in the northwest of New York State that he thought was well suited for a Norwegian colony. When he returned to Norway in 1824, Cleng gave a report on what he had found to the Quakers in Stavanger, and they began to equip an expedition to establish a Norwegian colony, a "settlement," in North America.

Cleng Peerson knew the Quaker Lars Larsson Geilane from Stavanger, originally from Time. The latter is identified as the initiator of the first known organized emigration from Norway to the United States on the sloop Restauration. The boat sailed from Stavanger on July 4 or 5, 1825 with 52 passengers on board, who were called "sluppefolkene” [“the sloop people” in Norwegian], and Sloopers in English.

The Sloopers landed in New York on October 9, where they were received by Cleng Peerson. They settled in the area that Cleng Peerson had located at Kendall, New York. It was an area with great population growth, and an important reason was the construction of the Erie Canal from the Hudson River to Lake Erie, which was completed in 1825.

The Sloopers remained in Kendall for a few years, but after Cleng Peerson surveyed conditions in the upper Midwest of Illinois in 1833, most of the settlers from Kendall moved to a new Norwegian settlement on the Fox River in LaSalle County west of Chicago in 1834–1835. With its founding, Fox River became a destination for Norwegian immigrants when regular emigration began in 1836. The upper Midwest thereafter became the main area of Norwegian immigration to the United States.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Excerpted and translated from source:

https://snl.no/Cleng_Peerson

Week 3: The Sloopers

Who were the passengers on the original Restauration?

The group of emigrants who decided to cross the Atlantic were Norwegian Quakers who sought religious freedom in America. 52 people boarded the sloop (the type of ship) Restauration and later became known in Norwegian as sluppefolkene or the sloop people. Americans refer to the passengers as Sloopers. There is a group called the Slooper Society of America that celebrates its ties to the sloopers.

Read more about the history of Quakers in Norway, and the names of the passengers and crew, here.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

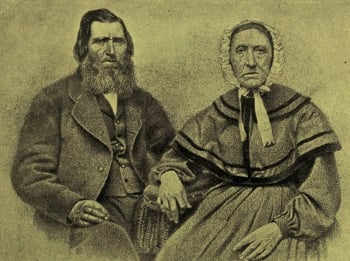

Photo: Sloopers Nils Nilson Hersdal and his wife Bertha

Week 4: The Sloop

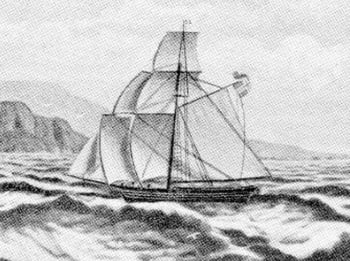

What is a sloop?

Sloop is a collective term for ships that are smaller in size, often called ship's boats, and often with sails.

Etymology: from Dutch sloep

Also known as sjalupp

Sloops are often associated with single-masted sailboats with snowsails, which carry the mainsail on the mast and the foresail on the stay in front. In recent times, this is associated with most sailboats in the Norwegian leisure fleet.

The Sloop was built in Hardanger in 1801 and was originally six commercial lasts or 12.48 tons burden. It carried herring to Gothenburg in Sweden and returned with grain from Denmark. It was first called Emanuel and later on, Håbet. In the 1820 Håbet had been enlarged and rebuilt in Egersund so that its burden became 18½ commercial lasts (or 38.48 tons) according to a certificate of measure dated at Egersund Oct. 5, 1820. The Sloop was then 54 feet long and 16 feet broad and drew 7½ feet of water. To commemorate its rebuilding a new name, Restaurasjonen, i.e. "the Restoration," was painted on it in Egersund Feb. 5, 1820. (pp. 15-16)

Berths had to be built for all of them (52 persons) on the lower deck.The deck area. allowing for the flare of the ship, could not have been more than 480 square feet, about 9 square feet per person. Assuming a minimum of space between bunks and tiniest of companionways, only 250 square feet was available for sleeping. Even with double bunks this was less than two-thirds the room needed, for 2½ by 6 foot bunks for all of the immigrants. Besides, space had to be provided for the chests containing their possessions and provisions.

On deck there was an abundance of fresh air but scarcely more room. The total area was only about 670 square feet. Allowing space for the galley, the companionway, water tanks, and lockers for fuel, sails, ropes, and the like, approximately 560 square feet remained for the 52 passengers.

"The Sloop was 2½ times as crowded as the Mayflower."

The Mayflower weighed 180 tons; was 90' long, 26' wide & at least twice as high as the Sloop (pp. 16, 18)

"According to American Law, a ship with 46 passengers (52, minus the crew) had to be at least 115 reg. tons to cross the Atlantic. The Restauration was only 38 reg. tons. Therefore, the authorities fined the group for overloading the ship. But after a petition to president John Quincy Adams, the case was dropped and the ship with its cargo was sold for 400 dollars."

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Source: https://snl.no/slupp

Week 5: What's behind the name

The Boat’s Name

On July 5, 1825 the sloop Restaurasjonen left Stavanger with 52 people aboard. This is considered to be the first organized emigration party to leave from Norway. In the different sources we find several ways of spelling the name of this ship, like Restauration, Restoration, Restaurasjonen and Restorasjon.

The boat was built in Hardanger as a yacht, named "Emanuel." Later it was rebuilt with a sloop mast and was named Restoration. The emigrants in Stavanger bought it in 1825, just months before they undertook what has since become one of the most famous voyages in Norwegian history.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Source:

https://www.norwayheritage.com/articles/templates/norwegian_settl.asp?articleid=31&zoneid=17

https://ryfylketrebaat.no/prosjekter/restauration/#:~:text=2010-,Historie,-Sv%C3%A6rt%20f%C3%A5%20hendingar

Map basis: Gunleif Seldal, and illustration by Jens Flesja.

Week 6: Route of the Voyage

The Route

In 1825, Restauration crossed the North Sea on a southwesterly course, passing through the English Channel, and continuing to Madeira. On this Portuguese archipelago west of Morocco, they stopped over and took on provisions before the captain set off west to cross the Atlantic.

The ship did not blow off course; it was never planned to sail a direct point-to-point route over the North Atlantic. In 1825, this southern arc was a common route for merchant ships sailing between Europe and America. It had its clear advantages in that it could take advantage of the trade winds and sail into a warmer climate. With the size and passenger load of the original 1825 Restauration, there would have been no way to carry sufficient foodstuffs and fresh water for 52 people without stopping over several times.

As of August 13, 2025, the modern Restauration is 40 days into its 97 day journey to New York. The ship is replicating the U-shaped voyage, having stopped in Cornwall, England, and hugging the coasts of France, Spain and Portugal to allow the ship to travel as near to land as possible, as well as occasionally dock and reload.

On the island of Madeira off the coast of Morocco, the crew had the boat drydocked (hoisted ashore and dried out) to have the hull checked for integrity prior to continuing westward to the Caribbean.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Week 7: Notes from the modern voyage

Sailing the Atlantic

On Restauration.no, crewmember Odd Kenneth Tollefsen reported that the first weeks on the ship “have been filled with powerful impressions, meaningful encounters, and not least, challenging weather.”

The crew faced near-gale conditions for many of these days, with the heavy winds and waves being a challenge to the crew and the ship itself. It has been a test of their skills, endurance and sense of humor.

Falmouth in Cornwall, England—a port that was visited on the 1825 journey—was a planned stop for the modern voyage. As it made its way to land, the ship was escorted to shore by a group of dolphins. The mayor of Falmouth welcomed the Norwegians with tea and cakes along with members of the Quaker community.

Next port was La Coruña, Spain where it was important to rest, repair and re-supply before continuing onto the Portuguese island of Madeira.

On this leg, the ship was met with rolling seas, high winds and rough conditions, but managed to sail quickly, with their cook creating meals while balancing on the ever-tilting floor of the galley. The ship arrived on the island of Madeira off the coast of Morocco on July 29th, where the crew had the boat drydocked (hoisted ashore and dried out) to have the hull checked for integrity prior to continuing.

Before launching westward into the Atlantic, the sailors of the Restauration acknowledged their voyage as “a living journey, bridging 200 years of emigration history with wind in the sails and stories to tell.”

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Photo credit: Jarvin - Jarle Vines, CC BY-SA 3.0

Week 8: Quakers in Norway

Quakers in Norway? How did that happen?

The history of the migrants who organized the voyage to America in 1825 reaches back to the Napoleonic wars between 1807 and 1814, when Norway was a dependent state under rule of the King of Denmark. The Danish Crown Prince—later King Frederick VI—sided with Napoleon, so his Norwegian subjects would often be captured and imprisoned by countries who opposed Napoleon.

While being held in British prisons, the captive Norwegians were exposed to new political and religious beliefs, such as Quakerism. A handful of Norwegians from the Stavanger area were released from prison and these new beliefs with others at home, building community among their own. The only problem was that the Lutheran Church of Norway did not allow for anyone to follow another faith. So, the Quaker dissenters were threatened and persecuted by their own government.

The Quaker leader who pushed to find out more about emigration to America was Lars Larsen Geilane. While interned on a prison ship in England, Geilane had converted, and went home to organize the burgeoning Quaker movement. His wife Martha Georgiana Jørgensdatter— later called Martha Larson—gave birth to daughter Margaret Allen Larsdatter during the 97 day crossing, bringing the passenger total up to 53. Settling in Rochester, NY, the family hosted thousands of Norwegian emigrés as they arrived to start a new life.

Not all of the passengers on the Restauration were Quakers; some were Haugean Lutherans who as another religious movement had also been persecuted for their beliefs and were eager to seek religious freedom in America.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Sources:

https://ryfylketrebaat.no/prosjekter/restauration/#:~:text=2010-,Historie,-Sv%C3%A6rt%20f%C3%A5%20hendingar

https://www.norwayheritage.com/articles/templates/norwegian_settl.asp?articleid=31&zoneid=17

"The Sloopers, Their Ancestry and Posterity" by J. Hart Rosdail, published by The Norwegian Slooper Society of America, 1961. Published by Photopress, Inc., Broadview IL.

Air-dried stockfish hangs on the modern Restauration, ready for use when the fish aren’t biting.

Week 9: Life on Board

Excerpt translated from: ryfylketrebaat.no

Seeing only the sea and sky for several months was probably a great strain. Of the 52 travelers, several had never been at sea before, and the days could be tough with bad weather and tempestuous seas. Faith then became important for the passengers, and daily gatherings for prayer and devotion were held.

Restauration measured 54 feet and was a very small ship for such a long journey. The passengers on board had about 1 square meter each below deck and the same amount above deck at their disposal. It was therefore important to be careful with hygiene on board, so that diseases would not spread.

We have not found any provisioning list and therefore do not know for sure what provisions the crew and passengers brought with them during the crossing. However, with few options for preservation and a limited selection of food and drink, one can find out what was common to take along on a crossing in the early 19th century.

When the sloop set sail from the dock in Stavanger in 1825, they did not know how long the journey would take. Hence it was necessary to bring food with a good shelf life. Enough water for the crew and passengers was the most important thing. This was stored in barrels and most often the captain was responsible for rationing the water.

On board the Restauration, Endre Salvesen Lindland was in charge of the cooking. They most likely brought along dried meat, salt cured meats and herring. Bacon, pork, salted herring and stockfish are on almost all provision lists from this period, so it can be assumed that this was the case on board the Restauration. In addition, there was flatbread, breadcrumbs, butter, cheese, prim (a sweet, spreadable variant of brown cheese), flour, sugar, peas, potatoes and cereals. To soothe the throat—in addition to water—milk, tea and coffee were most commonly used. Voyages in the early 19th century were made by sailing and the crossings could often be both arduous and difficult. It was not uncommon to have illnesses and pestilence break out on board. To combat illness, a little brandy, vinegar and a couple of bottles of wine and raisins and prunes for soup could be recommended to combat seasickness.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Photo: “Loam Margaret”

Week 10: The Sloop Baby

To add a little extra excitement to an already harrowing voyage, Martha Georgiana Jørgensdatter, pregnant at sea for 60 days, gave birth to her first child, a baby girl. As Martha and her husband were Quakers and Lars had been greatly influenced by his time spent in England, they named their baby Margaret Allen Larsdatter after an English Quaker woman.

Margaret Allen Larsdatter (later Larson) grew up in a Norwegian enclave in Rochester, New York, with her father working as a shipwright on the Erie Canal. The Larson home hosted hundreds of new immigrants as they made their way westward to parts Midwest.

As part of an art project by Jane Sverdrupsen, the crew of the modern Restauration has an artwork called “Loam Margaret” on board- which imagines what baby Margaret looked like when she was born between continents.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Sources:

https://lokalhistoriewiki.no/wiki/Margaret_Allen_Atwater

https://www.restauration.no/en/nyheter/artwork-loam-margaret-baby-born-1825-crossing-aboard-jane-sverdrupsen-september-2-2025

Photo: Norwegian settlers in front of their sod house in North Dakota in 1898. Photo taken by John McCarthy and collected by Fred Hultstrand. (A Milton, North Dakota, photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Week 11: Drømmen om Amerika – The American Dream

Norwegian North Americans think about where they came from and the roots that ground their family tree in a distant homeland. Similarly to North Americans, who like to trace their ancestry back to quaint farmsteads that their people left, there is a mirrored image of Norwegians who look toward America and Canada in memory and search of those who left. America fever, as it was known, saw 800,000 emigrants—a third of the Norwegian populace—depart for North America within just 80 years.

Where did their loved ones end up? Did they change their names and forget about those back home? Did they send letters and provide much-needed financial support?

Lars Kilevold, a composer, producer and renowned Norwegian pop musician known for cheeky 1980 societal statement songs like “Ute til lunch” and “Livet er for kjipt,” wrote and composed the musical “Drømmen om Amerika” with dramaturg Arne Lindtner Næss, creating a show that was staged across Norway throughout 2025.

The cast of this musical demonstrates the difficulty of packing up and saying goodbye to everyone you know to find a future somewhere else. “Drømmen om Amerika” recreates the story of the people who sailed courageously into the unknown for a chance at something better.

On Lars Kilevold’s website, you can view six of the songs from “Drømmen om Amerika,” with subtitles in English:

On a summer’s day in 1866, the ship Christiania leaves Oslo harbor to transport 350 emigrants across the Atlantic. As they follow the interwoven storylines of the captain, the ship’s mate, a wealthy widow, and a destitute stowaway, Asta, the audience sees that although the characters are sailing toward a common American Dream, they are not a monolith of immigrants, but rather a tapestry of diverse motivations and backstories. Together, they must weather the crossing, navigating fog, storms, lack of wind, travelers who fall overboard and a near-collision.

In tunes ranging from funk to waltz, Kilevold's songs weave humor, drama, action and romance into the storyline.

In the hope-filled opening song “Østavinden,“ The East Wind, passengers state some of the reasons for heeding the call of America: the promise of more fertile land, escaping poverty, embracing adventure, the prospect of love, adding that they “have more courage than sense.”

Asta the stowaway sings about her hope to becoming the best beggar in New York (Den Beste Tiggern i New York), where “everyone is rich.” One of the passengers, armed with a Norwegian-English dictionary, takes it on himself to misguidedly teach the rest of the ship some English in “Give Me More.” Barely intelligible, each English word is spoken following Norwegian pronunciation rules.

Listen to the full line-up of songs from “Drømmen om Amerika” on this YouTube Playlist.

On YouTube you can also watch a video of Asta and and the other passengers singing “Drømmen om Amerika” —the American Dream—aboard an actual boat.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrOOAFTG5lk

It has been 200 years since the first Norwegian group pooled their resources and departed for America. One can hardly fathom the waves of emigration that they set into motion. Around one in three Norwegians left their homeland over the span of 80 years.

There are now more descendants of Norwegians in the U.S. than there are Norwegians in Norway, and there is therefore an unusually close bond between these two nations.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Credit: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Week 12: Update from the Restauration’s log

Reposted excerpt, translated from Restauration’s Facebook.

End of the week, Sunday, September 21, 2025.

Restauration is on its way to Wilmington, NC. The crew and skipper on board are curious, what will they encounter there? Several of you may know the city and Wilmington, NC — [...]it is a city that itself carries a proud history from the American Revolution.

Here, the ship, skipper and sailors will be met by a population that knows the value of freedom, struggle and hope, and who have invited artists to create a monument to these very ideals. I see some similarities with the Free City of Stavanger. When Restauration docks, it is therefore more than a historical reunion—it is a meeting between two stories about the dream of a better life, told across seas and time. There is no evidence to support the notion that the emigrants stopped over here. However, the skipper has some words for you from the week on board.

Skipper Kjell Morten Ronæs has sent his end-of-week post:

We are approaching Wilmington, NC. About 150nm [nautical miles] left and there are three sailors waiting to board. Nils Helge, Espen and Trygve. Christian has chosen to disembark and visit his friends and family in the USA.

We will stock up on some fresh food to last us until the next leg, which is a short 4-5 days. Before the last leg towards Jersey.

The last few days have been a total zoo on board, with visits from birds of various species. They are very tame and we feed them, so they are ready to fly on. This adds a nice touch to everyday life. We also caught a barracuda that turned into delicious fish soup that Terje made. He is a master and can work wonders from a small supply of provisions.

The weather has also been unusual. From hot and scorching days, with light to fair tailwind. Then we had two days of thunder and booms, with lightning all over the horizon and rain showers that poured and pounded. We had to pull out our rain jackets again. The wind turned in all directions, and we had downwind sails plenty at times, but we do have propellers, so we managed to make some progress. After two days with "Thor's hammer" near us, the sun came out again along with a nice cool breeze. Then suddenly, the wind turned to the northeast, strong in the nice weather, and we lowered the sails. Adjusted the jib and headsail. The topsail got packed, way at the top. Chief Mate Halvor was like a monkey on the mast top platform. Packed the topsail better than ever, so we are ready for New York. So now it will be the propeller and the jib sail that provide propulsion.

We're taking a short break in Wilmington before we are forecasted to have a nice tailwind towards Atlantic City for a steady course towards New York.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Week 13: A Royal Reception

Unlike when the 1825 Restauration approached New York harbor, this year there will be much fanfare when the modern ship makes landfall. In fact, there will be a royal guest in attendance to greet the crew. Crown Prince Haakon Magnus will be a guest at the events, along with an array of Norwegian and American dignitaries, artists and members of the public.

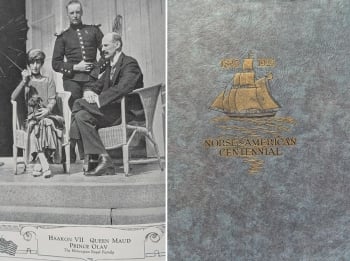

This is not the first time that royals have commemorated the 1825 crossing, however; for the 100th anniversary in 1925, crowds gathered at the Minnesota state fairgrounds for four days, June 6-9, with guests including King Haakon VII, Queen Maud and Crown Prince Olav along with representatives from Norway’s parliament, clergy and academia. On the American side were President Calvin Coolidge and First Lady Grace Coolidge; the governor-general of Canada, Lord Byng and his wife Lady Evelyn Byng, 13 members of congress from various states, and six governors and the Supreme Board of Sons of Norway. Bands and choirs from the Norwegian Lutheran colleges Augsburg, Concordia, Luther and St. Olaf and throngs of Norwegian Americans filled a stadium, singing “Ja Vi Elsker” and “Beautiful Savior.” Every Norwegian American affiliated organization seemed to be present.

The events were a showcase of the accomplishments of Norwegian Americans in their first hundred years in America, which were supported by the Minnesota State Legislature with $10,000 of appropriated funds: 22 special exhibits focused on pioneer and church life, schools, agriculture, Norwegian American newspapers, literature, public servants, art, charity, arts and crafts, music, societies, commerce, skiing, Sons of Norway, Daughters of Norway, medicine, industry, Norse-Canadians, engineering and architecture, and a Minnesota state exhibit. There were speeches, pageants, sacred services, music and much pomp and circumstance. The commemorative program was no fewer than 95 pages.

There was even a series of athletic events: a baseball bracket for the Lutheran colleges, a soccer game, bicycle race, a multi-day track and field meet, and an acrobatic exhibition.

At the 1975 sesquicentennial, events marking 150 years were centered around Leif Erikson Day in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis-St. Paul. Concerts, folk music and dance, worship services and dinners were among the events.

Distinguished guests included King Olav V, anthropologist and explorer Thor Heyerdahl who delivered the keynote address, agronomist Norman Borlaug, Norwegian American Hollywood actress Arlene Dahl, hotel executive Conrad Hilton, Olympic skier Stein Eriksen, Norwegian American governors Hubert Humphrey, Wendell Anderson, Senator Walter Mondale and Congressman Albert Quie, among many others. After the events, the Royal Family departed to pay visits to the Norwegian Lutheran colleges of the Midwest.

For information on events related to the 200th anniversary, visit the Crossings 200 website.

Follow the virtual voyage of the Restauration as we await the ship’s safe landing in New York and learn about the historic journey along the way!

Week 14: Welcome to America - A Celebration in Music

Bicentennial Program in New York

On the morning of Leif Erikson Day, the Restauration will arrive at Pier 16 in Brooklyn, New York after a stopover at the Statue of Liberty, concluding the ship’s 97-day voyage across the Atlantic.

An array of Norwegian musicians will be on the pier to celebrate the arrival, along with a host of Norwegian Americans, Sons of Norway members, dignitaries and artists. Here are some of the Norwegian musicians taking part in the welcome events:

Ragnhild Hemsing Trio

Get a glimpse of a tune that Ragnhild Hemsing will play at the commemoration event in New York. Hemsing plays both Hardanger fiddle and classical fiddle and will perform with her jazz trio after Crown Prince Haakon’s speech. Look for a recording of the performance that will be posted after 2 p.m. Eastern, on crossings200.no. Hemsing says that she inhabits both folk and modern traditions and will weave the sounds of Ole Bull, Edvard Grieg and folk music from Valdres into this modern jazz performance.

Astrid S

Astrid Smeplass is a singer-songwriter originally from the village of Berkåk in Gudbrandsdalen. She began writing songs in her teens and was signed for a record deal shortly thereafter. Over the summer, Astrid S received high praise for her performance of Norway’s national anthem at a women’s soccer match between Switzerland and Norway. Her third #1 hit in Norway is the 2025 Norwegian language cover, “Det regner i Oslo” - “It’s raining in Oslo.”

Kaizers Orchestra:

Alternative rockers Kaizers Orchestra from Bergen are a rare Norwegian band that sings in their native language while also achieving popularity beyond Scandinavia. This July, Kaizers Orchestra played a show in Stavanger to see off the Restauration, and will now welcome the ship to New York with an October 10 concert at Manhattan’s Town Hall. Legendary singer-songwriter Tom Waits referred to their music as “Thinking man’s circus music.” Listen to their tune Hjerteknuser (Heartbreaker), which has over 51 million plays on Spotify.

Randaberg Yngre Mannskor (“Randaberg Young Men’s Choir) was on the dock in Stavanger, wishing the modern Restauration a safe journey to America. Like a melodic reflection, the group will also be in New York, performing at the welcome events and even at a benefit concert.

Fjellkoret, a choir from Bergen, performed a dramatized musical concert “Det Løfteriket Landet” (The Promised Land) in Stavanger as the Restauration left Norway’s coast. At that show, they announced that they would be performing it in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in the fall. Watch their performance in the famous cathedral in the heart of New York City that took place October 7th. The concert includes songs about immigration, peace, friendship, reflection and freedom.

Image Credit:

Jens Flesjå – voyage map

Gunleiv Seldal – base map

For Friends of the Restauration Association