In the mid-1800s an outbreak of Amerikafeber (America fever) struck in Norway and rapidly spread over the country. The sloop vessel Restauration had set sail in 1825 for America, carrying 52 passengers. These weren’t the first Norwegians to migrate, but the first large group. Most of these immigrants were Quakers drawn by the promise of religious freedom, inspiring comparisons to the Mayflower. Sailing from Stavanger in July, the boat landed in New York 97 days later. The “sloopers” put down roots in western New York state, and as letters arrived home, news of their success in the New World created a frenzy in the homeland that was stoked throughout the 19th century.

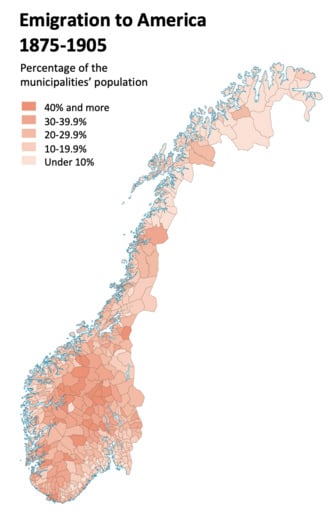

A map of Norway that shows how many Norwegians emigrated to the U.S in the period 1875-1905. Translated version. Original from norgeshistorie.no

Emigrés wrote home with details of finding plentiful work and a decent income. These letters were known as Amerikabrev (letters from America) and according to research by Thor Indseth, were the main source of information for the general Norwegian populace, covering everything from the price of land and dry goods to the quality of the soil.

Word spread quickly that the U.S. government was promising 160 acres of “free land” to anyone who would colonize the Midwest. This is how many of the Norwegian immigrants got established in Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas and beyond.

Still, passage was expensive and risky. What made people want to leave the only land they’d known and chance everything to start all over in the New World?

In the mid-1800s, Norway had fallen on rough times. A doubling in population between 1800 and 1850 meant that most sons were not going to inherit farmland, and that Norway’s already-strained agricultural production would have a hard time keeping the populace fed.

If marriage prospects were low, young rural women had few options. If there were too many mouths to feed at home, unmarried women and girls would be sent to work as tjenestepiker (servant girls) on larger farms. That way they would earn room and board along with a small income. Sometimes boys also found work as farmhands elsewhere.

Emigration opened new opportunities for young people to improve their lot in life. More and more decided to heed the call of America and take their chances. Similar to immigration today, those who arrived first often sent prepaid tickets and money home to sponsor the passage for friends and relatives.

In addition to letters, America fever also spread through music. Songs told of the excitement of the new World, and of the drawbacks. These were known as emigrantviser or utvandrerviser: emigrant songs. Common themes are the heart-wrenching goodbye from loved ones, the treacherous voyage across the sea, impressions of the new country and longing for home. Elin Prøysen recorded an album of these tunes that is available on Spotify. You may recognize the melody to Oleana, a hyperbolic song about the high life in America, where ”The grain plants and cuts itself, and all you do is sit and wait.”

Sometimes young Norwegians came to the U.S. to work for other Norwegians who had migrated before them. Housekeeping, farm work, lumber mills, fishing and construction were common occupations for newcomers with little to no English skills.

“A farmer from Houston County, Minnesota, returned [to Stavanger] on a visit the winter of ’70-’71. He infected half the population in that district with what was called the America fever, and I, who was then the most susceptible, caught the fever in its most virulent form. No more amusement of any kind, only brooding on how to get away to America. It was like a desperate case of homesickness reversed.”

In total, 860,000 Norwegians came to the U.S. between 1820 and 1925, roughly a third of Norway’s populace. Today around 4.5 million Americans consider themselves to have Norwegian heritage.

Recollections of an Immigrant by Andreas Ueland is available to read in PDF format.